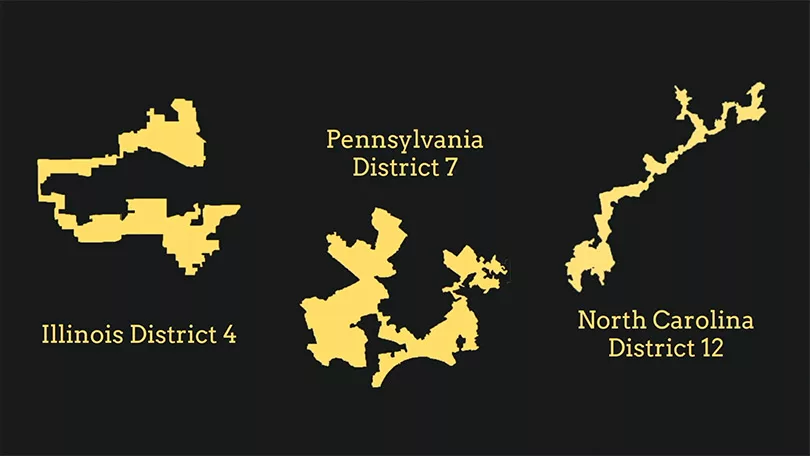

Gerrymandering occurs when district lines are redrawn, often in distorted, complex shapes, in an attempt to manipulate election results and disenfranchise voters. Gerrymandering gets its name from Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry, who, in 1812, signed a bill creating a district that looked like a salamander, which was then mocked as a “Gerry-mander.”

The Census, Community Districting, and Gerrymandering

Every 10 years the United States does a population count, called the Census. The Census is used to determine political representation and allocate federal funding. Each state also uses Census data to determine how to divide its population into equal Congressional and local election districts, through a process called community districting or redistricting. This is intended to make sure that everyone’s vote has equal weight in electing representatives – but when districts are gerrymandered, that’s no longer the case.

Racial Gerrymandering

Gerrymandering comes in many different forms, the most notable of which are racial and partisan gerrymandering. In racial gerrymandering, districts are drawn to dilute – or, in some cases, amplify – the representation of certain racial groups.

For the most part, the Supreme Court has taken a hard stance against racial gerrymandering. A key enforcement provision of The Voting Rights Act prohibited states from dividing communities of color, and courts have time and time again struck racial gerrymandering down as unconstitutional. But, with the Voting Rights Act’s enforcement provision no longer in place, states are free to draw district lines without first making sure that those districts are not discriminatory. Racial gerrymandering is once again becoming a common tool to disenfranchise and suppress people of color.

Partisan Gerrymandering

Partisan gerrymandering, on the other hand, is used by both Democrats and Republicans to dilute the amount of representation the opposing party can gain or amplify their own representation. So far, the Supreme Court has ruled that partisan gerrymandering is legally permissible, despite its negative impacts.

The U.S. Department of Justice used to review how districts were drawn, and sometimes they required states to redo unfair districts. However, the Supreme Court ruled in 2019 that the Justice Department doesn’t have to review districts anymore, and if districts are drawn based on politics, Congress or the states themselves have to fix that. But the states created the problem, and some members of Congress were elected from gerrymandered districts, so we can’t rely on those groups to make the process more fair.

Packing and Cracking

There are two main methods to gerrymandering – “packing” and “cracking.” When a gerrymandered district is “packed” in a partisan way, people of Party A are drawn into one district, while Party B supporters are spread across many districts. Even though Party A will likely win their district, they’ll only win one district, while Party B will likely win the rest and have a majority. “Cracking,” on the other hand, refers to splitting people up so that their candidate is unlikely to get a majority in any district.

Effects of Gerrymandering

The effects of gerrymandering are widespread. Underrepresentation is obviously one impact of cracked and packed districts. Poor communities and communities of color are disproportionately impacted by gerrymandering, and as a result, their political power is diluted.

Gerrymandering also leads to political monopolies and increased partisanship. Gerrymandered districts can be used to protect politicians already in power by making their districts less competitive, and once redistricting happens, it can take up to ten years before lines can be drawn again. When districts are gerrymandered to be less competitive between multiple viewpoints, representatives do not have to compromise on hard-line stances in order to win seats. Fair representation requires a healthy push-and-pull that isn’t present in gerrymandered districts.

What can we do to fight gerrymandering?

– Hold your state legislators accountable when new district lines are drawn, and let them know you want fair representation for everyone. Attend town halls, participate in local politics, and contact your representatives by phone or email to share your feelings about gerrymandering.

– Advocate for federal protections against gerrymandering, like the For the People Act.

– Register and vote in local and state elections for candidates that not only represent diversity and justice, but actually champion it. Never miss an election: sign up for Rock the Vote’s election reminders.

Published March 14, 2022