What is the 19th Amendment?

The 19th Amendment makes it illegal to deny the right to vote to any citizen based on their sex, which effectively granted women the right to vote. It was first introduced to Congress in 1878 and was finally certified 42 years later in 1920.

The Amendment’s official certification date is August 26; however, it’s not uncommon for the Amendment to also be celebrated on August 18th — the anniversary of when Tennessee ratified it.

Did the 19th Amendment enable all women the right to vote?

On paper, the Amendment protected discrimination against all women, but in practice, it only gave white women the right to vote. Black women, Native American women, Asian American women, and women from other racial and ethnic minority groups were discriminated against for 45 more years until the passage of The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA). The VRA afforded crucial protections to Black, Indigenous, and Women of Color (BIWOC) voters. And, women with disabilities only gained protections in 1990 with the Americans with Disabilities Act.

What led to the 19th Amendment?

During America’s early history, women were denied many basic rights granted to their male counterparts. For example, women were not legally permitted to own property, nor were they allowed to vote to have representation in our government.

Achieving women’s suffrage — the right to vote — required a lengthy and arduous struggle that took nearly a century of conferences, protests, hunger strikes, speeches, court cases, lobbying, organizing, and marches.

What happened at the Seneca Falls Convention

The Seneca Falls Convention, held in 1848 in Seneca Falls, New York, was largely organized by local Quakers, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Lucretia Mott. Advertised as “a convention to discuss the social, civil and religious condition and rights of women”, it was the first women’s rights convention in the United States. It earned widespread attention, was attended by men and women, and inspired many similar conventions.

The Declaration of Sentiments, modeled after the Declaration of Independence, was introduced, debated, modified, and signed by 100 of the 300 attendees (68 women and 32 men). A major debate took place on whether to include women’s suffrage in the document. Frederick Douglass, who was the convention’s sole African American attendee, argued for its inclusion and the resolution was retained.

By the National Women’s Rights Convention in 1851, conventions were annual events and a central tenet was women’s suffrage. The outbreak of the Civil War derailed the suffrage movement, but only temporarily.

What/Who inspired the Seneca Falls Convention?

The Haudenosaunee, a confederacy of six nations that reached in close proximity to Seneca Falls, frequently interacted, taught and even adopted early European settlers into the tribe giving them “dual citizenship”. The Haudenosaunee governance structure, a democratic confederacy, inspired many local settlers as it required everyone in the nation – men and women – to have a voice in decision-making through consensus in public councils.

Despite the spread of the colonists’ patriarchal views, the Haudenosaunee maintained equal treatment of men and women and in many cases regarded women superior to men. Women had predominance in daily life with elevated roles in spirituality, governing, agriculture, and children bearing. They had the ability to work in the fields, own property, and have custody of their children. Women selected the chiefs and were integral to Haudenosaunee spirituality as the Haudenosaunee creation myth revolves around a Skywoman.

The three women’s rights activists who spearheaded the Seneca Falls Convention, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, and Matilda Gage all had ties to the Haudenosaunee people and often referenced the Haudenosaunee culture’s equal and superior positioning of women in writings and interviews.

Matilda Gage, who was adopted by the Haudenosaunee and gained dual citizenship, drew parallels between the oppression of women and Native people and eventually became a Native rights activist. Lucretia Mott wrote about witnessing women exercising equal authority in decision-making in Haudenosaunee governance structures. Elizabeth Cady Stanton referenced her early interactions with Haudenosaunee people, including the adoption of her cousin and neighbor into the Haudenosaunee Nation and drew on Haudenosaunee customs to inform some of the proposals in the Declaration of Sentiments.

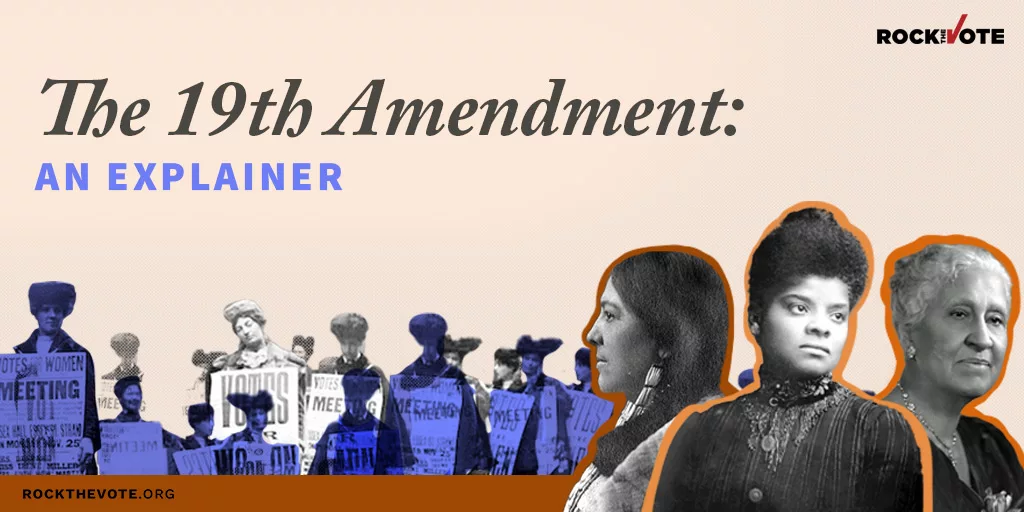

Was the suffrage movement a white women’s only movement?

No, in fact, the role of Black suffragettes is one of the most untold stories in the passage of the 19th Amendment. Black women worked closely with white women from the earliest years of the suffrage movement.

Sojourner Truth gave her “Ain’t I a Woman” speech in Akron, Ohio at the National Women’s Rights Convention in 1851.

Prior to the Civil War, Black and white abolitionists and suffragists joined together as allies making the U.S. women’s rights movement closely tied to the antislavery movement. Free Black women abolitionists and suffragists were active and assumed leadership positions at multiple women’s rights gatherings in the 1850s and 1860s.

Black men, such as Frederick Douglass, Charles Lenox Remond, and Robert Purvis, also joined Black suffragettes and worked closely with white women’s rights activists William Lloyd Garrison, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony.

That said, the women’s suffrage movement did experience tensions and fractures over race, particularly with the introduction of the 15th Amendment. And, while Black suffragettes played a pivotal role in the passage of the 19th Amendment, they remained without a practical right to vote following its adoption and were often limited to non-leadership positions in civil and voting rights organizations where their voices were limited and sometimes even ignored.

The Suffrage Movement and the End of the Civil War

After the Civil War, women’s suffrage became entangled with the meaning of citizenship and the expansion of rights of formerly enslaved Black men. The American Equal Rights Association (AERA) was formed by former abolitionists and women’s rights activists to endorse both women’s and Black men’s right to vote.

The introduction of the 15th Amendment, which would theoretically enfranchise Black men, but not any women, led to the deterioration of interracial, mixed-gender coalitions, and splintered the women’s suffrage movement. The choice between universal rights or accepting the priority of Black male suffrage led to the creation of two major organizations in 1869 — The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and The American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA).

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony formed the NWSA, which argued for universal suffrage and opposed the proposed 15th Amendment arguing that Black men should not receive the vote before white women creating tensions with notable Black leaders, such as Frederick Douglass. The NWSA advocated for a range of reforms to make women equal members of society and sought to pass a Constitutional amendment for women’s suffrage.

Julia Ward Howe, Lucy Stone and her husband Henry Brown Blackwell led the AWSA, which supported the 15th Amendment. The AWSA gained popularity by focusing exclusively on suffrage. The organization also included prominent male reformers as leaders and members and pursued a state-by-state strategy to pass women’s suffrage.

Black women cited Black male suffrage as an important component of their suffrage goals. Black suffragists became members of both organizations. Hattie Purvis joined NWSA. Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Charlotte Forten, and Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin joined the AWSA.

The largest women’s organization at the time, The Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), established in 1873, joined the general suffrage movement giving the effort an enormous boost.

At the local level, suffragists made several attempts to vote and after being turned away filed lawsuits hoping to bring the matter to the U.S. Supreme Court. Susan B. Anthony successfully voted in 1872 but was later arrested and found guilty for voting in a highly publicized trial that helped fuel the movement. In 1875, in Minor v. Happersett, the Supreme Court upheld states’ rights to deny women the right to vote recognizing the plaintiff as a citizen but stating that the constitutionally protected privileges of being a citizen did not include the right to vote.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, many state, regional and local suffrage groups were formed to increase support at the local and state levels, with many of these organizations founded by Black women who were not being fully welcomed or recognized in national organizations.

Tensions between prominent leaders, including Douglass and Stanton faded and in 1890, the NWSA and the AWSA merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). This new organization’s mission was to lobby women’s voting rights on a state-by-state basis.

Women’s Suffrage in the States

It’s worth noting that New Jersey recognized women’s right to vote in 1797; however, women were stripped of their voting rights in 1807 when the state passed allowing only free white males the right to vote.

In 1869, Wyoming territory granted women the right to vote motivated less by gender equality and in large part by the hope that the law would attract women to the territory which had a 6:1 men to women ratio. The territories of Utah, Washington, and Montana were among the first and passed women’s voting rights during the 1870s and 1880s.

In the six-years following the formation of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) in 1890, Colorado and newly formed states of Wyoming, Utah, and Idaho adopted amendments to their state constitution granting women the right to vote.

At the start of the 20th century, there was a renewed momentum to the women’s suffrage movement with more states extending voting rights to women, including 22 states prior to 1920.

Activism on the National Stage

In 1916, the National Women’s Party (NWP) was formed by the merging of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage and the Women’s Party. With prominent leaders, Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, the NWP’s tactics were more attention-grabbing and militant than the more moderate approach of the NASWA.

Following a January 1917 meeting with President Woodrow Wilson, the NWP launched what became a two and a half year protest outside the White House involving a total of more than 2,000 women who picketed and went on hunger strikes. The protesters became known as the Silent Sentinels because of their unique, silent protesting tactics. During these two and a half years, women were harassed, beaten, arrested, and served jail time.

During the first year of their protest, on November 14, 1917, imprisoned suffragists were clubbed, beaten, and tortured. W.H. Whittaker, superintendent of the Occoquan Workhouse — a prison farm — ordered nearly 40 guards to brutalize imprisoned suffragettes, including Lucy Burns, Dora Lewis, and Dorothy Day. Newspapers carried the stories dubbing the event the “Night of Terror” galvanizing more public support for the movement.

Passage of the 19th Amendment

First introduced to Congress in 1878, the women’s suffrage amendment failed several times. In 1915, the amendment failed again without President Wilson’s support.

The United States’ entry into WWI, in 1917, helped to shift public opinion about women’s suffrage and role in the country. NASWA argued women should be rewarded with the right to vote for their patriotic wartime service.

In 1918, another bill was introduced, this time with President Wilson’s support. The 1918 Suffrage Bill passed the House with only one vote to spare but failed the Senate by two votes.

With increasing pressure from the public, lawmakers in both parties were anxious to pass the amendment and make it effective by the 1920 general election. To try and get the amendment passed in time for the next year’s election, President Wilson called a special session of Congress and in the spring of 1919, The House of Representatives passed the amendment followed by the Senate just a few months later.

The amendment was then submitted to the states for ratification, where it would require the approval of 36 states (three-fourths of states) to be adopted as a Constitutional Amendment. Within just a few days, several states ratified the amendment since their legislatures were actively in session. Additional states ratified at a regular pace until March 1920 when the number of states stalled at 35 for five months.

In the summer of 1920, the Tennessee State Senate voted to ratify the amendment, but the State House of Representatives still had to vote. A young state representative, Harry Burn, wore an anti-suffragist pin and voted against the amendment in what would be a tie vote. Harry had been internally conflicted so when a letter from his mom was delivered to him in the chambers before the revote, he took her advice. His mother urged him to “be a good boy” and vote for the amendment. In the revote, Burns cast the tie-breaking vote making Tennessee the 36th state to ratify the amendment allowing it to be adopted.

The 19th Amendment was adopted and officially became part of the U.S. Constitution on August 26, 1920. 100 years ago.

From 1920 to Today

In 1920, NAWSA formed an organization that continues today, The League of Women Voters of the United State (LWV) — a Rock the Vote Partner with over 800 state and local Leagues.

Following the passage of the 19th Amendment, Black women, Indigenous women, Asian American Women, women from many races and ethnicities and women with disabilities faced discrimination and voter suppression. It wasn’t until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990 that prohibited discrimination against all women regardless of race, ethnicity or disability status, that women’s right to vote was protected; however, with the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision on Shelby Co. v Holder decision in 2013 all voter protections are at risk.

Today, dozens of national women’s rights and advocacy organizations exist with thousands more at the state and local levels. Despite being the majority of voters, women are still underrepresented in our government, particularly Black women, Indigenous women, Latinas, Asian American women, women from all racial and ethnic minorities, and women with disabilities. Women have incredible power to determine the direction of our communities, our country, and our democracy, particularly young women. The anniversary of the 19th Amendment marks a milestone in an ongoing story of progress that requires us to show up and to keep pushing forward.

Published August 22, 2022.